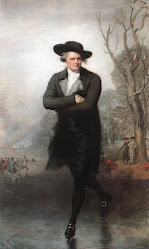

Horace, a very young and up-coming lawyer was painted by Stuart in 1800, and one day some 50 years later, as an older man, he talked to his nephew about the portrait. This nephew wrote down these reminisces with his uncle in a diary, which was then later shared with George Mason, biographer of Stuart “The Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart” 1894 ... and I share them in their entirety with you here. Enjoy the insight into our artist: his particular mode of painting, issues of concern, and ... how happy he was to not be a Tailor!

Binney, Horace

From the diary of the late Horace Binney Wallace, a nephew of Mr. Binney, I am permitted to make the following extract:

“Wednesday, June 31st, 1852. I called today upon Mr. Binney, before leaving town for the summer. The conversation turned upon Stuart’s portrait of him, which hangs in our back parlor. He said that it was painted in the autumn of 1800, when he was not twenty-one years old. Some one had brought out from Canton some Chinese copies of Stuart’s Washington, and Stuart prosecuted an injunction in the Circuit Court of the United States against the sale of them. ‘I was sedulous,’ said Mr. Binney, ‘in my attendance on the courts, and here I became acquainted with Stuart. He came frequently to my office,’ continued Mr. Binney, ‘which was in Front street. I was always entertained by his conversation. I endeavored to enter into his peculiar vein, and show him that I relished his wit and character. So he took snuff, jested, punned and satirized to the full freedom of his bent.’ “Binney’ he said to one of my friends, ‘has the length of my foot better than any one I know of,’ meaning, I suppose, that I knew how to humor him, and give him play.

“ ‘When your mother requested me to give her the portrait that is in your house, I made an appointment with Stuart, and called to give my first sitting. He had his panel ready (for the picture is painted on a board), and I said: ‘Now, how do you wish me to sit? Must I be grave? Must I look at you?’ ‘No,’ said Stuart; ‘sit just as you like, look whichever way you choose; talk, laugh, move about, walk around the room, if you please.’ So, without more thought of the picutre on my part, Stuart led off in one of his merriest veins, and the time passed pleasantly in jocose and amusing talk. At the end of an hour I rose to go, and, looking at the portrait, I saw that the head was as perfectly done as it is at this moment, with the exception of the eyes, which were blank, I gave one more sitting of an hour, and in the course of it Stuart said: ‘Now, look at me one moment,’ I did so. Stuart put in the eyes by a couple of touches of the pencil, and the head was perfect. I gave no more sittings.

“ ‘When the picture was sent home,’ continued Mr. Binney, ‘it was much admired; but Mr. T***** M***** observed that the painter had put the buttons of the coat on the wrong side. Sometime after this, Stuart sent for the picture, to do some little matter of finish which had been left, and, to put an end to a foolish cavil, I determined to tell him of M.’s criticism; but how to do it without offending him was the question. The conversation took a turn upon the excessive attention which some minds pay to the minutie of costume, etc. This gave the opportunity desired. ‘By the way, said I, ‘do you know that somebody has remarked that you have put the buttons on the wrong side of that coat?’ ‘Have I?’ said Stuart. ‘Well, thank God, I am no tailor.’ He immediately took his pencil and with a stroke drew the lapelle to the collar of the coat, which is seen there at present. ‘Now,’ said Stuart, ‘it is a double-breasted coat, and all is right, only the buttons on the other side not being seen.’ ‘Ha!’ said I, ‘you are the prince of tailors, worthy to be master of the merchant tailors’ guild.’

“ ‘Stuart,’ said Mr. Binney ‘had all forms in his mind, and he painted hands, and other details, from an image in his thoughts, not requiring an original model before him. There was no sitting for that big law-book that, in the picutre, I am holding. The coat was entirely Stuart’s device. I never wore one of that color [a near approach to a claret color]. He thought it would suit the complexion.’

“ ‘On the day when I was sitting to him the second time,’ said Mr. Binney, ‘I said to Stuart, ‘What do you consider the most characteristic feature of the face? You have already shown me that the eyes are not; and we know from sculpture, in which the eyes are wanting, the same thing.’ Stuart just pressed the end of his pencil against the tip of his nose, distorting it oddly. ‘Ah, I see, I see,’ cried Mr. Binney.

“Mr. Binney agreed with me in thinking that the Washington was one of Stuart’s least inspired heads. Stuart used to call that head, you know, his ‘hundred-dollar bill.’ One day, when he had his family at Germantown, and his painting room in the city, learning from Mrs. Stuart that the domestic treasure was empty, he set off to come to town, to his bank, for one hundred dollars. At a tavern, half-way, got out of the stage to get something to drink, and in searching his pocket-book found a fifty-dollar note, which he had forgotten that he had. When the coachman called upon him to get into the coach again, he replied, ‘You may go on; I mean to wait for the return coach.’

“ ‘Stuart,’ Mr. Binney caid, ‘thought highly of his portrait of John Adams. Showing it one day to Mr. Binney, ‘Look at him,’ said he. ‘It is very like him, is it not? Do you know what he is going to do? He is just going to sneeze.’

“ ‘Stuart had an anecdote illustrative of physiognomy—its truth or falsehood. There was a person in Newport celebrated for his powers of calculation, but in other respects almost an idiot. One day, Stuart, being in the British Museum, came upon a bust, and immediately exclaimed to his companion, who was also a Rhode Island man: ‘Why, here is a head of Calculating Jemmy.’ He called the curator and said: ‘I see you have the head of Calculating Jemmy here.’ “Calculating Jemmy!’ said the curator; ‘that is the head of Sir Isaac Newton.’ "

The portrait of Mr. Binney above described, Mr. John William Wallace gave back to his uncle in his old age. It is a picture of a youth of twenty years, having a high complexion, bright chestnut-colored hair and splendid blue eyes. Hon. Horace Binney died in 1875, aged 96 years.

8

*

Professional Career:

Founding member of the Hasty Pudding Club

Founding member of the Law Library Company of the City of Philadelphia;Director, 1805-1819; 1821-1827

Assembly of Pennsylvania, member, 1806-1807

1st U.S. Bank, Director, 1808

City of Philadelphia, Common Council, president, 1810-1812

City of Philadelphia, Select Council, member 1816-1819

Founded the Apprentices' Library 1821

Associated Members of the Bar of Philadelphia, Vice Chancellor, 1821

Law Association of Philadelphia, Vice Chancellor, 1827-1836; Chancellor, 1852-54

Law Academy, President,1832 Member of the U.S. Congress 1833-1835

*

*

Horace Binney by Gilbert Stuart

National Gallery of Art DC

from Lawrence Park:

Honorable Horace Binney

1780-1875 A son of Dr. Barnabas and Mary (Woodrow) Binney of Philadelphia. He was graduated from Harvard College in 1797, admitted to the Philadelphia bar in 1800 and became one of the most prominent lawyers of the country. He obtained his LL.D. Harvard, in 1827. He was a member of the American Philosophical Society; of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and a Fellow of the American Academy.

John Adams by Stuart

National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C

about to sneeze?☺

about to sneeze?☺

♥

.jpg)